Renée Stout

by Ade Ofunniyin

The Halsey Institute is honored to carry Dr. Ade Ofunniyin’s voice forward with this essay. Dr. O transitioned to join the ancestors on October 7, 2020. Dr. O was a frequent Halsey Institute collaborator whose powerful mind, unflinching devotion to the community, and ready laugh will be deeply missed. Thank you, Dr. O.

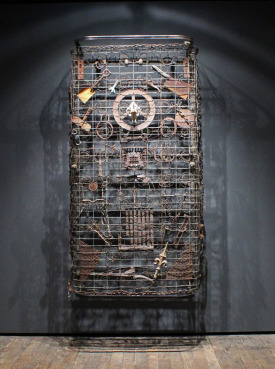

Renée Stout’s artistic renderings give elemental spirits breath and air—an uncanny terrain, a place she calls the “land of cosmic slop,” a “parallel universe.” Stout’s masterful use and display of her paintings, fabricated handiworks, and found and collected objects lead viewers on a journey into an unfamiliar consciousness and vibrational frequency. Her works evoke recessed memories: thoughts of people, places, and things, some of which might have been forgotten a long time ago, either erased or dismissed as obsolete.

In this space of ancestral remembrance, all things are possible. You will likely hear the musical sounds of Sly and the Family Stone’s “You Can Make It If You Try” or Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Keep Your Head to the Sky.” In cosmic-slop Ville, metamorphoses abounds, featuring a master soundtrack by Sun Ra and his Arkrestra theme song to the Afrofuturist science-fiction film “Space Is the Place.”

Stout masterfully employs and deploys a sundry of mnemonics to orchestrate a symphony of images that conjure the memories and spirits of her ancestors, affirming that “our ancestors matter.” Her creations serve as vessels for the hope and aspirations of Africa and her diasporic descendants, the remembrance of those “things that were stripped from our inner-being.”

She deliberately imbues her creations with objects, concoctions, and spirit-filled remembrances that are intended to inspire and influence deep impressions of the power of conjure and ancestral relations. Memories are often held in the things that were dear to the those who are to be remembered. The African soul recalls and understands the call back to itself. The soul will always remember that the person who is that soul matters. Drumbeats, voices in song and praise, and body motions that give way to dance, dance, dance are essential to gaining entrance into Stout’s parallel space; it is a space of transformation and serenity, quiet and equanimity.

Stout affirms again, “We were forced to be present and always engaged in being fearful; always having to create new ways of survival; [we have had] very little time for peace and projection. We have been called a lot of different names … always pushing us away from who we were and who we are, Africans.” Her work pushes toward a solid reclamation of the knowingness, power, and wisdom of Africa’s spiritual sciences, those unseen and intrinsic powers that reside in natural elements and inanimate objects. Old Africans knew and employed the powers that live inside of herbs and plants, rocks and water.

The artist’s altars are unapologetic repositories of the history of African people. It is a history of simultaneous magnanimity and conquest, a history rooted in displacement, a history of forced movements and disenfranchisements, a history recalling the capture and enslavement of human beings, lands, continents, and natural resources … a history of domination and oppression. Never being able to “feel completely at home in this country where I was born,” Stout conjures places in her mind, heart, and hands, finding the visions, temperament, and tools she needs to locate her sacred space, where peace reigns supreme, and the ancestors are welcomed.

Renée Stout

Born in Junction City, Kansas (1958)

Lives and works in Washington, D.C.

Renée Stout grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and earned her BFA from Carnegie Mellon University in 1980. Originally trained as a painter, she moved to Washington, D.C. in 1985 where she began to explore the spiritual roots of her African American heritage through her work. In 1993, Stout became the first American artist to exhibit in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art.

Stout’s work is included in such collections as the Afrika Museum, Berg en Dal, Netherlands; Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; San Francisco Museum of Fine Art, CA; National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, and National Museum of African American History and Culture, all in Washington, D.C. Stout is the recipient of such awards as the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Award (1991 & 1999), Anonymous Was A Woman Award (1999), the Joan Mitchell Painters & Sculptors Grant (2005), and the Women’s Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award (2018), among many others.

Renée Stout’s work was featured at the Halsey Institute in 2013 in Tales of the Conjure Woman. A catalogue by the same title was published by the Halsey Institute in 2015.

Ade Ofunniyin

Dr. Ade Ofunniyin was a Charleston, South Carolina native. He earned a BA in Social Science from Fordham University and an MA and Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Florida.

Ofunniyin was the Founder and CEO of The Gullah Society, a nonprofit 501(c3)organization created to assist those seeking to reconnect with their Gullah heritage, African history, and culture. Ofunniyin’s work sought to restore neglected cemeteries and uncover the histories of local Charleston citizens, artists, artisans, and craft people. The Gullah Society states, [w]e honor our ancestors and commit to attending to their burial grounds as we know that they are forever with us.” Ofunniyin was also the founder and co-owner of Art and Remedies Wellness.

Ofunniyin was a cultural anthropologist, author, playwright, artist, and curator with a special interest in economic empowerment and community development, multiculturalism, and diversity. His interest grew out of his awareness of systemic racism and inequalities in academic institutions, politics, and businesses.

He was the grandson of the legendary Charleston artisan Blacksmith, Philip Simmons. Ofunniyin apprenticed in his grandfather’s blacksmith shop and developed an appreciation for historic preservation, restoration, and the ways that artisans, artist, and craft people are represented in Lowcountry history.